Vocal fatigue: the facts

Strictly speaking, our voices don't tire. Voice, after all, is air from the lungs chopped and shaped and carried in waves to the listener's ear. Our structures that create the voice, however, can tire, work inefficiently or become damaged from overuse.

Symptoms include:

- Dry mouth;

- A need to clear your throat;

- Hoarseness;

- "Scratchy" or raw feeling;

- Achy feeling in your neck;

- Feeling winded;

- A general feeling of weakness when speaking;

- Frequent breaths or running out of breath;

- Reduced volume on high or low pitches;

- Tension in the neck, shoulders and upper chest.

Right now, science can provide no magic number for recovery time needed to overcome vocal wear and tear. A big obstacle is the huge range of vocal "robustness" among people.

Are your vocal muscles tired? Infrequent or hard exercise makes our muscles ache. The same goes for muscles required for voice. The muscles around the ribs (intercostals) and abdomen expand and contract to provide breath for speaking. Loud or excessive talking may make these muscles tire. Some people then fall into the unhealthy habit of overusing muscles of the neck to "push" the voice. These little muscles can't fully and consistently do the work of the big muscles of the abdomen and rib areas. Thus, the neck muscles are worn out before the teaching day is over.

Muscles tire as "good" chemicals (nutrients, etc.) are consumed and waste products (lactic acid) build up in muscle fibers. Our blood flow transports nutrients to muscle fibers and carries away lactic acid. Because our circulatory systems work constantly, chemicals exchange fairly quickly. Thus, people recover from muscle fatigue fairly easily.

Cell wear and tear: When you feel your voice dragging at day's end, consider:

- human vocal folds collide 100-1000 times per second;

- vocal folds collide many hundreds thousands times per day;

- increasing pitch and volume increases vocal fold friction;

- high or loud talking makes vocal tissues tire faster;

- most teachers speak frequently each day, five days a week;

- teachers get limited recovery time (quiet time) during the workday.

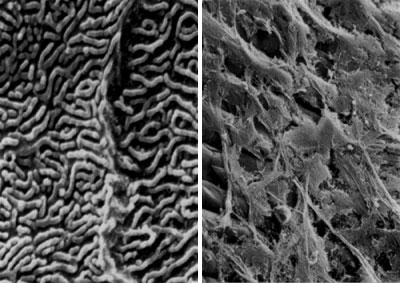

Nowhere else in the body do tissues have such mechanical demand. The body's response is to protect: vocal nodules or cysts may form. While these growths cushion the blow, they also make vocal folds vibrate less efficiently. Even the safest and most healthful talking or singing causes destruction vocal fold cells. Vocal cells must constantly replace old, damaged cells with fresh ones. Quiet time, or recovery time, is necessary for regeneration to keep pace with destruction.

Relief from the research lab? Joint research at the University of Utah and Michigan Sate hopes to replicate vocal fold cell destruction and recovery in lab dishes. By growing small samples of cells in the laboratory, specialized equipment can imitate the vibration and stresses that the cells would experience in the body during speech. Stressed cells can then be scrutinized as they attempt to recover. Early results indicate that damaged

tissues produce cells that are less pliable and thus vibrate less efficiently. This seems to reinforce the common sense notion that -- following damage --we must give our bodies adequate time to heal.

No smoking...please

Smoking is all-around bad news for your voice.

Cigarettes keep voice-producing tissues constantly irritated, and over time, tissues change as a protective mechanism. This is why heavy, long-term smokers' voices are often low in pitch.

Smoking marijuana is even worse, burning as hot as 400 degrees.

Smoking lowers the pressure in the valve joining the esophagus to the stomach, sometimes allowing stomach acids to "back up" in the throat and onto delicate voice tissues.

If this isn't bad enough, be aware that 85 percent of head and neck cancers are linked to tobacco use. Smoking cigarettes is a major contributor to the most devastating laryngeal disease diagnosis a person can receive: cancer.

At the very least, smoking decreases lung function. Without good lung power, more stress is placed upon the larynx when speaking or singing.

An auditory vacation

Did you know that music can be an excellent stress reducer? Tension is an enemy of easy, healthful vocalization.

Keep your cell phone well-stocked with restful music for moments when you need a lift. It's easy to store bunches of melodies of your choice, at a minimal cost.

Many advocate classical music (especially Mozart) as a stress-buster, but experiment with spiritual, country, jazz, blues or rock and roll. Or, install an app with nature sounds (such as rainfall or the ocean) to lift your spirits and deflate those tense muscles.

Recovery by the numbers

When it comes to recovery time, professional athletes have it made. Sports medicine research identifies appropriate recovery times for different stresses on body tissues:

- Professional basketball players play every two to three days;

- Baseball pitchers hit the mound once every three to four days;

- Title-contending boxers compete once or twice a year.

A general rule in the field of athletic training: Recovery times need to match the amount of localized tissue injury that has occurred. (Note: This does NOT mean recovery time needs to match performance time.) Acute damage to joints, ligaments, tendons, and other connective tissue, may take days, weeks or months to recover. Recovery from general muscle fatigue, though, is usually quick.

Even the most healthful speaking leads to wear and tear of voice tissues. Usually, our bodies cope with the housekeeping and repair tasks well. But the high vocal demands of teaching may push the vocal system over the edge. New research may soon help teachers through the day by identifying the best balance between talking (lecturing) and non-talking (student-managed) activities. For example, what would the healthiest pattern during a two-hour block of teaching?

1) Talk 60 minutes, recover 60;

2) Talk 30 minutes, recover 30 minutes, repeating the pattern twice;

3) Talk 10 minutes, recover 5 minutes, repeating the pattern eight times.

Early results show that even small vocal "naps" (#3 above) interspersed with speaking reduces vocal fatigue.

A vocal diary: Teachers need not wait for scientific research to provide specific guidelines for voice recovery. Rather, we encourage informal experimentation on your own. Develop a simple vocal diary. Track voicing activities (including any episodes of screaming or yelling), hormonal cycles, symptoms of reflux disease, sleep adequacy, off-duty voicing demands, weather conditions, illnesses, allergies, alcohol use and other relevant factors.

Why is my voice so tired? As a teacher, your voice is your primary professional tool. Just for fun, let's consider how rigorously you use that performance tool as compared to another type of professional, for example, a pro bowler. Let's imagine that a serious bowler plays a couple games each day, six days per week. In bowling, the actual set-up and release of the ball is pretty quick, with periods of inactivity while the bowler waits for the pins to reset, the ball to return or a competitor to perform. Thus, in an average game, the bowler may spend 10 minutes or so actually performing. If we calculate the bowler's performance time per week, we find that - out of the 10,080 minutes each week - the bowler performs about 120 minutes. To discover a bowler's rest to performance ratio, we divide non-performance time (10,080 - 120) by the performance time (120) . We find a rest to performance ratio of 83 to 1.

A teacher, on the other hand, usually works five days per week. Assume that a teaching day is 7 hours (420 minutes). [According to research, the average teacher speaks cumulatively about one full hour.] However, teaching younger children or subjects that require extensive speaking (i.e., foreign language teachers) usually requires more talking. If you coach or direct other extracurricular activities, factor those minutes also.

1. Estimate the number of minutes you spend speaking each working day and multiple it by 5 (working days). Subtract from 10,080 to discover your non-performance time =

2. Divide that number by your performance time = ___

3. Do the math (or grab a calculator). What’s your ratio?

Most teachers find that they ask their bodies to significantly out-perform professional athletes.

Some food for thought

Research shows that even though teachers work about seven hours a day, they actually talk only about one cumulative hour on the job. Is 1 of 24 hours in a day too much talking?

Consider: what do you do when you're not teaching? Sit at home and say nothing? Probably not. The same type of person who is attracted to the teaching profession (outgoing, helpful, comforting, social) is also drawn to activities that may be vocally demanding. Whether you use your voice on the job or off, it's still the same voice.

And then there are the compulsive talkers. Some people use speech as an outlet for emotional overload: anxiety, unhappiness, anger, giddiness. Some individuals seem to feel obligated to fill silences with ummms, ok's, sure's, or similar phrases. They literally talk away the day. All the added speaking can make your daily word count skyrocket.

Some strategies for healthy vocalization have more to do with your ears than lips.

Take for example, the Lombard Effect. It's simply your adjustment of vocal loudness according to the loudness level you hear. You've likely noted the comical, overly loud manner in which a person wearing a Walkman speaks. Consider situations when the Lombard Effect has influenced your speech: chatting in cars or restaurants; social gatherings; the classroom. How many times have you found yourself Some strategies for healthy vocalization have more to do with your ears than lips. Remember: loud talking is particularly taxing to the vocal tissues. We theorize that some people may be hyper-sensitive to the Lombard Effect, and may be speaking at a volume far above what is truly necessary to be heard. In other words, don't overdo the Lombard.

Are you susceptible to the Lombard Effect? How loudly we speak is so closely related to the volume of what we hear that we often try to "talk over" background noise without even thinking about it. Try it for yourself: how would you say, "Students, please be seated," inside the quietness of the school's library? Now, say the phrase imagining you are in the noisy school cafeteria. Did you feel the difference?

Vocal cell wear and tear: After looking at the microscopic slides of vocal tissues below, you'll likely better understand the concept of vocal cell destruction. The image on the left was made before the experiment began. After four hours of constant phonation, look at the after effects of the same tissue (right). - from the laboratory of Dr. Steven Gray.

Tell me more about vocal fatigue

Vocal fatigue is an unwelcome component of many teachers' days. To fully explore the topic, a fictional teacher poses a few questions to our voice experts.

Q: You've talked about fatigue in the muscles and vocal fold tissues. But you haven't said anything about other vocal structures: cartilage, ligaments, tendons and joints. How well do they hold up?

A: Although they've been studied less, joints, cartilage, tendons and ligaments of the vocal system seem to be less prone to fatigue as compared to muscles and vocal fold tissues. An exception would be a teacher suffering from arthritis. An important joint of the vocal system - the cricothyroid joint - may stiffen and have less range of motion in a person with arthritis.

Q: You implied that the circulatory system helps vocal muscles recover from fatigue pretty quickly. So, is it reasonable to conclude that we recover from muscular fatigue quicker than tissue fatigue?

A: Yes. Muscles recover within a few minutes, but cell replacement in the vocal folds takes 2-3 days.

Q: Okay, so muscles recover quicker, but are they more prone to fatigue than tissues are? In other words, which type of fatigue should teachers be most worried about?

A: A teacher should probably be most concerned with tissue fatigue. It's usually fairly easy to take a 10-minute break to allow waste products to be swept away and nutrients to be carried into muscle tissues. It's much more difficult for a teacher to comply with 2-3 days of vocal rest!

Q: What should I do if I feel some of the signs of vocal fatigue coming on?

A: Ideally, a teacher will habitually avoid long monologues to prevent undue vocal tissue destruction. If you feel fatigue creeping in and your day of teaching is not yet complete, keep a stash of activities handy for students: ten minutes of quiet independent reading, group or partnered activities, work stations, or student recitations.

Q: Common sense tells me that under-conditioned respiratory muscles used for speaking could be strengthened with aerobic exercise, such as running. True?

A: It is true that "breathing is breathing" and well-conditioned intercostal and abdominal muscles benefit the teacher. However, consider the difference in the way we breathe for exercise and for speaking. In aerobic exercise, we breathe in and breathe out in approximately equal proportions. In speaking, however, we usually take air in fairly quickly, but then release air in a slow, controlled manner.

Q: I know there are different types of muscle fibers: some move rapidly, while others are best for sustaining movement. Would a certain exercise regimen improve the mix of muscle types used for prolonged speaking?

A: There is probably no better exercise for speaking than to speak. At the same time, you know that speaking too much or in an unhealthy manner can be destructive. What a balancing act! At the heart of this contradiction, consider:

- Know your own body and its limitations

- Correct unhealthy vocal habits

- Try to make your vocal environment as friendly as possible

Q: Okay, what else can I do to facilitate recovery from vocal fatigue?

A: Allow yourself be a "vocal coach potato" sometimes. Would you be surprised if a marathon runner insisted on recovery time after a big race? Along these lines of thinking, teachers may need to let their voices rest. Tell your family and friends that you need vocal downtime. Try to find activities geared toward relaxation and rest. We live in a busy and complicated society, but you may need to tell yourself it's okay to take a day to rest.

Q: So, does this mean I should whisper or talk very softly so I don't tire my voice too much?

A: Many experts may tell you that whispering is "bad" for your voice, yet we could find no definitive research to support that claim. Whispering is essentially talking without vibration of the vocal folds, and if the vocal muscles are fatigued, whispering won't allow them to rest. Whispering may also have a dehydrating effect. While there is some disagreement among experts about the wisdom of whispering, it is safe to say that whispering is not the same thing as vocal rest.

Q: We all know it's bad to burst a blister and that calluses form on your hands for a reason. Following that same line of thought, is it good or bad to remove vocal growths?

A: It depends. Vocal nodules may respond well to therapy, and thus, no vocal fold microsurgery would be needed. For stubborn nodules and most polyps, a combination of voice therapy and surgery may be recommended. Of course, these decisions should be made in conjunction with a physician and speech-language pathologist with experience in voice.